In Part I of this series, we proposed a simple method for launching a child process with a fake command line and then modifying its command line before it started executing. Due to its simplicity, this method comes with one major drawback: because we are modifying the buffer where the command line is located, the “real” command line must be no longer than the “fake” one.

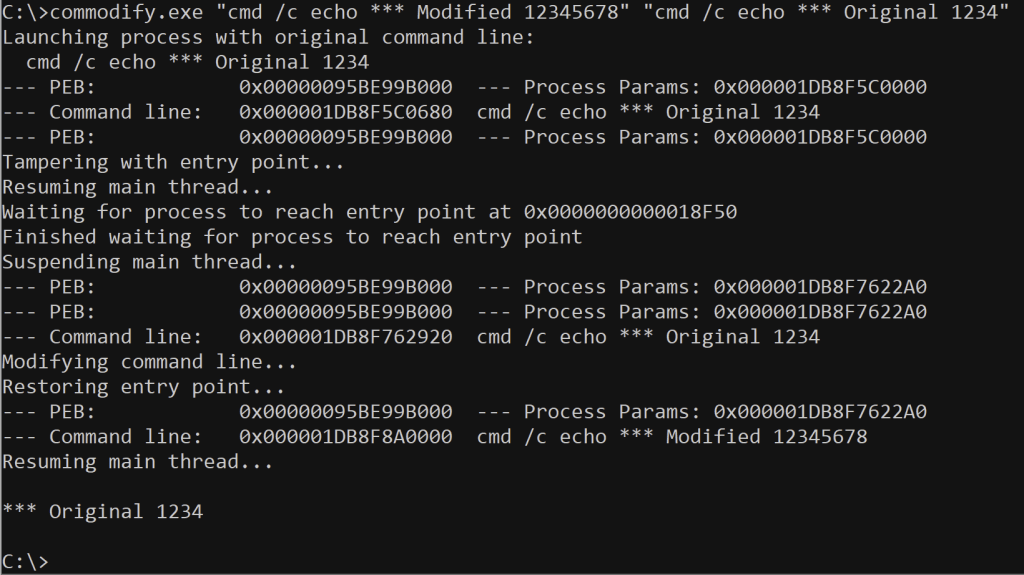

The following screenshot demonstrates our tool in action, using the “In Situ” modification method. We launch a process with an “Original” command line, and then modify it to a longer, “Modified” command line. We can see the output at the end, which indicates that the modified command line was successfully run, although the output was truncated as the command line buffer could not accommodate the entire desired string.

We suggested that the length constraint may be mitigated somewhat by inserting space characters into the fake command line, however this itself might indicate to a vigilant observer that something is not quite right and warrants further investigation. So, let us now see if we can modify the tool to allow arbitrary-length command lines.

The following code, enclosed within a function, will allocate a new block of memory within the target process address space, copy the command line to this new memory block and update the pointer to the buffer to point to it.

BOOL ModifyCommandLine(HANDLE hProc, PEB64 *pPeb, RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS64 pParams, LPCWSTR szNewCommandLine) {

UNICODE_STRING64 cmdLine= pParams->CommandLine;

SIZE_T nNewCmdLineLen = wcslen(szNewCmdLine);

cmdLine.u.Length = (WORD)(nNewCmdLineLen * 2);

cmdLine.u.MaximumLength = pParams->CommandLine.u.Length + 2;

cmdLine.Buffer = (QWORD)VirtualAllocEx(hProc, nullptr, cmdLine.u.MaximumLength, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

LPVOID pCmdLineAddr = &(((RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS64*)pPeb->ProcessParameters)->CommandLine);

WriteProcessMemory(hProc, pCmdLineAddr, &cmdLine, sizeof(UNICODE_STRING64), &sLen);

}

That looks simple enough. Unfortunately though, when we run this code, we start seeing strange behaviour. Depending on how we ran the application, we might see a popup message, indicating that “The application was unable to start correctly (0xc0000142)”. The error code 0xc0000142 appears to mean DLL Initialization Failed.

Interestingly, if we examine the popup window, we find that it is owned by the csrss.exe process. We know that this is a privileged system process, and that it is involved in process creation. Could it be that it is detecting tampering with the command line? Or, taking our cue from the specific error code, could our tampering be interfering with the initialisation of the standard DLLs that are loaded into each newly created process, presumably with the involvement of csrss.exe?

This might make for an interesting investigation later, but we won’t dwell on it for now. However, if we examine the PEB of the application after it has started running, and compare it with its context immediately after the creation of the process in its suspended state, we do notice something curious – the address of the Process Parameters structure has changed, as has the address of the buffer containing the command line string. It appears that something has copied or moved these structures in memory. However, our replacing the command line pointer with a freshly allocated memory address has somehow interfered with this. Again, we won’t dwell on the why, but, for now, accept this as a given, and figure out how to get around it.

We know that each executable file has an Entry Point address, indicating where the program starts. However, this is not actually the very first instruction that is executed in the main program thread. The first executed instruction belongs to the function LdrpInitializeProcess within ntdll.dll. Between there and the actual process entry point, there is a good deal of initialisation going on, and it seems that something in this initialisation is copying the Process Parameters to a different location.

Because all this process initialisation code is boilerplate, and identical across all processes, it should not actually depend on anything in the command line. So, perhaps it’s just best to wait for all this initialisation to complete, and to modify our command line where it truly matters — once control hits the entry point of our process.

To achieve this, I used a little trick I found documented in an article on DLL injection. In short, we temporarily modify the code at the entry point, replacing it with a simple JMP instruction that loops back in on itself. We allow the process to run, and periodically poll the main thread to check whether its instruction pointer is at the entry point. Once it has reached the entry point, we suspend the thread, restore the original code, and do whatever it is we need to do (in this case, tamper with the command line) before finally resuming the thread again.

Not entirely elegant, and it might cause one CPU to run at full throttle for a short while, but it does the job.

I won’t share the entire code used to achieve this in this post, but assuming we’ve written some functions to do the heavy lifting, we’ll have something like the following. The ModifyCommandLine function referenced below is the same as the one shown above.

BYTE originalEntryPointInstructions[2];

pEntryPoint = FindEntryPointAddress(hProc);

ModifyEntryPoint(hProc, &peb, ¶ms, pEntryPoint, originalEntryPointInstructions);

ResumeThread(hThread);

while (!IsThreadAtEntryPoint(hThread, &peb, pEntryPoint))

Sleep(500);

SuspendThread(hThread);

ReadPeb(hProc, &peb, ¶ms);

ModifyCommandLine(hProc, &peb, ¶ms, szRealCommandLine);

RestoreEntryPoint(hProc, &peb, ¶ms, pEntryPoint, originalEntryPointInstructions);

ResumeThread(hThread);

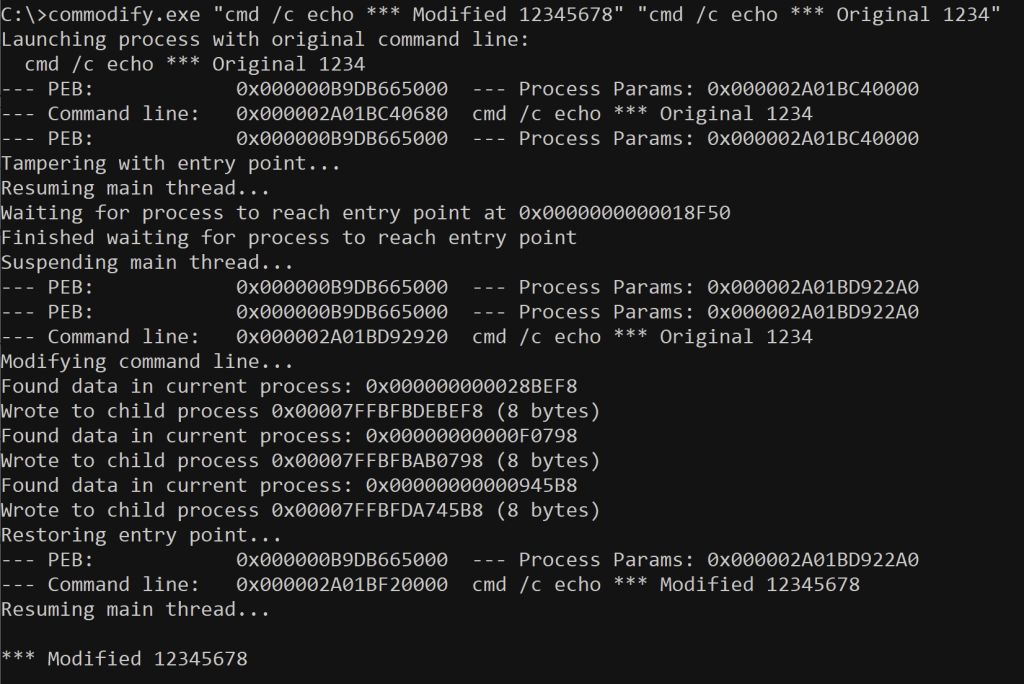

Running our modified tool (with additional logging statements inserted), we observe the following output:

We see here that the command line seems to have been successfully modified, and that its entire length has been written. But yet, when the process finally runs, it still echoes the value contained within the original command line. How can this be?

Let’s think about how a normal Windows application (written in C or C++) might access its command line. There are two key ways in which this can be done:

- Using the

GetCommandLineA()orGetCommandLineW()API functions provided by kernelbase.dll, which can be called from anywhere within the application. - Via the pointers provided by the

argvargument to themain()orwmain()entry points in a non-graphical (console) application. - Via the pointer provided by the

pCmdLineargument to theWinMain()orwWinMain()entry points in a graphical application.

If we examine the disassembly of the GetCommandLineW() function within the kernelbase.dll file, we find that this is not reading the command line from the pointer referenced by the PEB, but is using a pointer stored within a separate global variable. Locating the initialisation code provided by kernelbase.dll, we can see that it simply copies this pointer over from the Process Parameters structure. Only the pointer is copied. GetCommandLineA() is slightly more complicated — obviously the string must be converted to single-byte characters, so a new buffer must be allocated for this purpose.

So, this explains the problem we are seeing. Because we have waited for the target process to hit the application entry point, we have already allowed the initialisation code to copy the original command line pointer to another location. Substituting in a new command line at this point is already too late.

At this point, we need to go and replace the global pointer in kernelbase.dll with the new pointer as well. Using the Windows API, we can find where any given module has been mapped into a remote process address space. Then, we can scan the memory within that module for any occurrences of the original pointer, and replace those with the new pointer.

The code necessary to do all this is too complex for a blog post, but can be examined in the GitHub repository accompanying this article.

Suffice to say, when we perform this substitution in kernelbase.dll, we find that GetCommandLineW() now returns the correct pointer. If our application relies on this function to read its command line, this is all that must be done.

Returning to the case of wmain(), it turns out that the work of parsing the command line and generating the argv array is performed at a point after the application’s entry point, but before the execution of the wmain() function itself. This suits us because we’ve already modified the PEB-derived command line before this happens. However, it turns out that the pointer used for this operation has been pre-cached in yet another location, by one of the ucrtbase.dll or msvcrt.dll libraries. So, we’ll have to perform the same treatment for those modules as we did for kernelbase.dll — seek all instances of the original pointer and replace those with the new.

Testing the final product, we finally achieve our desired result.

So, at this point, we’ve achieved a tool that can modify the command line for a large number of executables. Seeing as the “official” process command line is expressed using 16-bit Unicode characters, this is most easily achieved only for applications which themselves operate on the Unicode version of the command line. We have not yet attempted to extend this for single-byte-character command lines, which would be more challenging indeed.

Similarly, for now we’ve only targeted applications written in C or C++, built using Microsoft tools and run against Microsoft’s “release” runtime libraries. Still, a good start, and a solid improvement on our initial effort.

I intend to release the full source code of the tool described here. This will include better error handling and all the functions not explicitly listed in the article. The source code will be linked from this article once it is made available.