In previous posts, we have explored some techniques for tampering with the command line of a freshly launched Windows process. In Part I, we saw a simple technique which suffered from the drawback that the new command line could be no longer than the original. In Part II, we proposed an alternate technique which supported command lines of more arbitrary length (subject to the UNICODE_STRING structure’s string length constraint of 32766 characters). This technique suffers from its greater complexity — because it is forced to wait until the process entry point is reached before making the substitution, it must take into account the possibility that the command line pointer was copied, and that the string itself may have been converted into other character formats. We solved the easiest of these cases — that of an application using Unicode characters and compiled against standard runtime libraries — while acknowledging that further work would be necessary to adapt to other scenarios.

From a programmer’s and hacker’s perspective, this was not an extremely satisfying result. We want to be able to inject command lines of arbitrary length into our target process, but we also want to do this while the process is suspended on its initial launch. Therefore, we must come to a better understanding of that mysterious error which we saw, and worked around during Part II of this series.

Let’s recap exactly what we did.

- We launched the process in a suspended state.

- We read the Process Environment Block (PEB) and the Process Parameters structure.

- We allocated a new buffer within the target process address space, and copied our new command line into that buffer.

- We resumed the main thread in the target process.

Let’s also recap our main observations.

- The process reported an error code of 0xc0000142, which means DLL Initialization Failed.

- By the time that control had reached the process entry point, the addresses of the command line buffer and the Process Parameters structure itself had changed.

It is strange indeed that the data seems to have been copied or moved. So, perhaps we can figure something out by debugging the process. My debugger of choice for this investigation will be x64dbg. To maintain continuity with the previous posts, I will continue to debug the cmd.exe executable, running it with the following initial command line:

cmd.exe /c echo *** Original 1234

Because we expect that the behaviour we’re seeking is occurring before the process reaches its entry point, we should be able to get the same results with any other executable or command line.

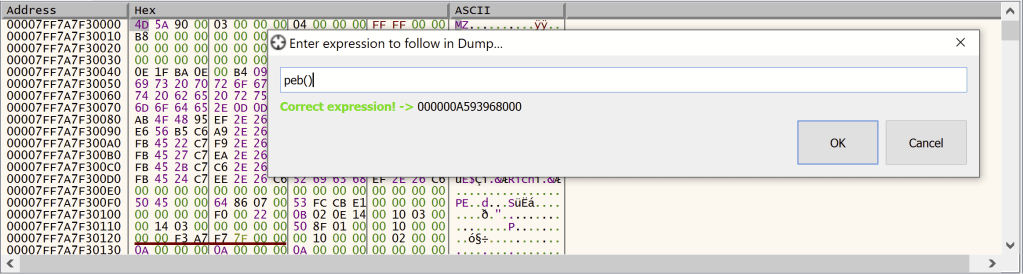

We set up the debugger to run the above command line, and allow it to break at the very first instruction executed by the main thread (remember, the process entry point is still well in the future). At this point, the Process Environment Block is already set up, so we locate it using the debugger’s peb() command.

We know that, on the x64 platform, the pointer to the Process Parameters is found at offset 0x20 of the PEB, so we note the current pointer at that address, and set a hardware breakpoint to break when the data at that location is modified.

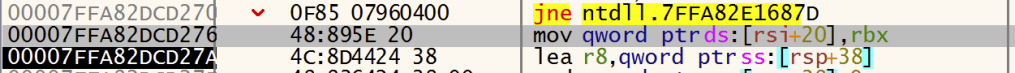

Allowing the program to run, we do find that the pointer is changed in a function named RtlpInitParameterBlock(). It turns out that this is not a long function, so let’s work our way though it. At the point the breakpoint hit, we find that the contents of the rbx register are being assigned to the ProcessParameters field of the PEB.

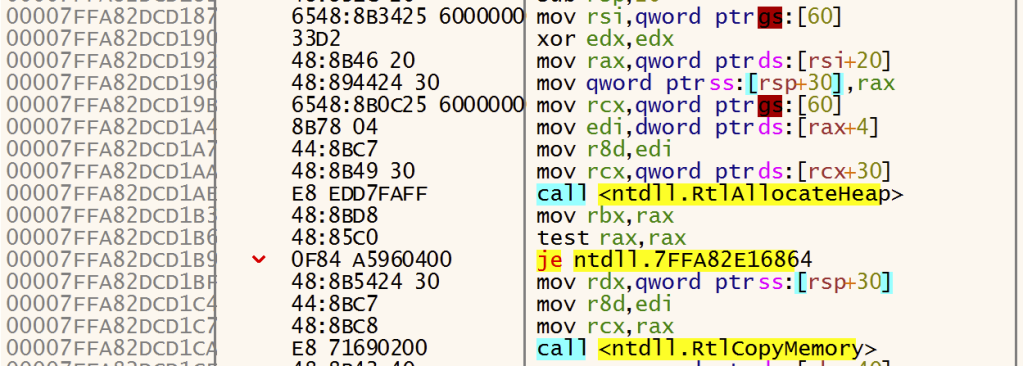

So, the rbx register contains the address of our new Process Parameters block. We can confirm this by working our way backwards in the function, and find the rbx register receiving the return value of a call to RtlAllocateHeap(). The same value is used as a parameter to RtlCopyMemory() several instructions later.

At this point, probably the most interesting parameter to RtlAllocateHeap() is the Size parameter, which will be passed via the r8 register. We see that this value, a DWORD, is itself read from offset 0x4 of a structure whose pointer is located at offset 0x20 of another structure. We’ve seen this offset 0x20 recently, and it turns out that it is indeed our very same Process Parameters structure.

So, it turns out that the size of the buffer containing the Process Parameters structure is stored near the beginning of the Process Parameters structure itself, an area marked by Microsoft official documentation as “Reserved”. However, this size is somewhat larger than the size of the RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS64 structure itself. It looks like the Process Parameters is indicating the presence of some data beyond its end. So let’s have a look in the debugger at what’s there.

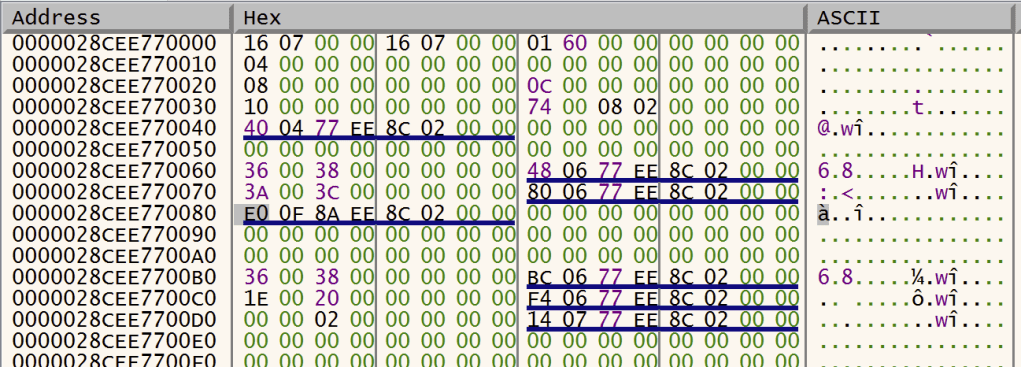

In this example, our offset 0x4 indicates a supposed length of 0x716 — much longer than the officially documented size of 0x80. Looking beyond offset 0x80, we see what appears to be a pointer, followed by some zeroes, followed by 3 UNICODE_STRING structures, followed by more zeroes. But if we look towards the very end of this buffer, we find something interesting.

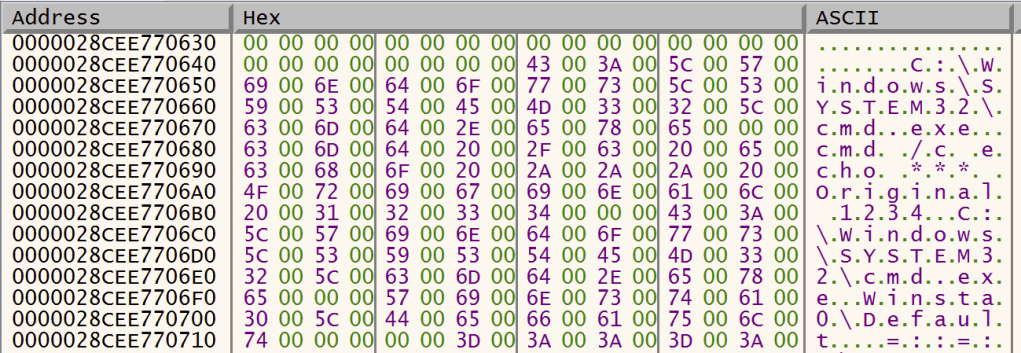

Looks like we have a few null-terminated, Unicode strings here. Indeed, these turn out to be our executable path name, our command line, our executable path name again, and the name of the default interactive window station. Looking back at offset 0x78 which should point to our command line, we do find that this does indeed point there (in this instance, 0x28cee770680).

So, we can see quite clearly that a copy of the entire buffer is made, string buffers and all. On closer examination of the remaining code within this function, we find that, after copying the data in a single operation, it then adjusts all the relevant pointers in the new Process Parameters structure, so that they point to the appropriate buffers within the new structure. Because the contents of the structures are the same, this is just a matter of simple pointer arithmetic — calculate the difference between the start of the old buffer and the start of the new buffer, and add this difference to all the pointers in the new buffer.

This explains our error. We allocated a new buffer for our command line, which was well outside the Process Parameters buffer. When the entire contents of the buffer were copied, this pointer remained intact. But the act of adjustment rendered the pointer useless. Most likely, it would end up referencing an invalid memory region.

So, armed with this knowledge, we can now propose a more elegant solution, which we express in the following code:

SIZE_T sLen = 0;

SIZE_T nNewCmdLineLen = wcslen(szNewCommandLine);

PROCESS_BASIC_INFORMATION pinfo;

NtQueryInformationProcess(hProc, ProcessBasicInformation, &pinfo, sizeof(pinfo), (DWORD*)&sLen);

// Read the PEB.

PEB64 peb;

ReadProcessMemory(hProc, pinfo.PebBaseAddress, &peb, sizeof(peb), &sLen);

// Read the length of the Process Parameters buffer.

DWORD nOriginalProcessParamsLen;

ReadProcessMemory(hProc, &((DWORD*)peb.ProcessParameters)[1], &nOriginalProcessParamsLen, sizeof(nOriginalProcessParamsLen), &sLen);

// Allocate a local buffer to store the contents of our Process Parameters buffer.

DWORD nNewProcessParamsLen = nOriginalProcessParamsLen + ((nNewCmdLineLen + 1) * 2);

LPBYTE pNewParamsBuffer = (LPBYTE)malloc(nNewProcessParamsLen);

RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS64 *pNewParams = (RTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS64*)pNewParamsBuffer;

// Read the contents of the original Process Parameters byffer, into our new local buffer

ReadProcessMemory(hProc, (LPVOID)peb.ProcessParameters, pNewParamsBuffer, nOriginalProcessParamsLen, &sLen);

// Allocate a new buffer in the remote process.

PTR64 pNewParamsAddr = (PTR64)VirtualAllocEx(hProc, nullptr, nNewProcessParamsLen, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

// Copy the new command line to the end of the new Process Parameters buffer

wcscpy_s((LPWSTR)&pNewParamsBuffer[nOriginalProcessParamsLen], nNewCmdLineLen + 1, szNewCommandLine);

// Adjust the buffer size at the beginning of the Process Parameters structure (first two DWORDs)

((DWORD*)pNewParamsBuffer)[0] = (DWORD)nNewProcessParamsLen;

((DWORD*)pNewParamsBuffer)[1] = (DWORD)nNewProcessParamsLen;

// Set the command line pointer to the address at the end of the buffer.

pNewParams->CommandLine.Buffer = pNewParamsAddr + nOriginalProcessParamsLen;

pNewParams->CommandLine.u.Length = nNewCmdLineLen * 2;

pNewParams->CommandLine.u.MaximumLength = (nNewCmdLineLen * 2) + 2;

// Loop through all 64-bit values within the buffer. If any of those are found to be within the bounds of

// the original Process Parameters buffer, adjust them to the equivalent offsets in the new buffer.

for (DWORD offset = 0; offset < nOriginalProcessParamsLen; offset += sizeof(PTR64)) {

PTR64 value = *((PTR64*)(&pNewParamsBuffer[offset]));

if (value >= peb.ProcessParameters && value < (peb.ProcessParameters + nOriginalProcessParamsLen)) {

*((PTR64*)(&pNewParamsBuffer[offset])) = (value - peb.ProcessParameters) + (PTR64)pNewParamsAddr;

}

}

// Write the new buffer to the remote process

WriteProcessMemory(hProc, (LPVOID)pNewParamsAddr, pNewParamsBuffer, nNewProcessParamsLen, &sLen);

// Write the address of the new buffer to the PEB of the remote process

WriteProcessMemory(hProc, (LPVOID)(&pinfo.PebBaseAddress->ProcessParameters), &pNewParamsAddr, sizeof(PTR64), &sLen);

free(pNewParamsBuffer);

As always, the above code has been presented with simplicity in mind, and omits bounds and error checking that should be present in a robust implementation.

This code works beautifully, and because it makes all necessary adjustments before a single instruction is executed in the target process address space, it is resilient against any copies or reformattings applied during the initialisation of the process. For the same reason, it should no longer matter that the program was compiled against Microsoft C runtime libraries. The only thing lacking for now is a 32-bit implementation.

We have now developed a robust tool for performing command line manipulation, but this is by no means the end of the series. Future articles will explore the effectiveness of these techniques for EDR evasion, as well as additional things we can achieve through this technique.